Productivity

Productivity has been getting a lot of attention recently and for good reason. We thought it would be a great opportunity to explore this topic in a bit more depth.

What is productivity?

Put simply, productivity measures how efficiently inputs (say, labour, capital or raw materials) are used to produce outputs (goods or services).

Productivity growth occurs when the economy finds new and better ways of using its resources, including through discovering and investing in new technologies, shifting resources to better uses, and increasing the skills of its workforce. Productivity growth is not about working harder or longer, but rather smarter to produce more.

Here is a simplified example. Rob currently makes hand-made watches. He can make 100 a month, working a 40 hour a week. He makes $100 profit on each one, therefore he makes $10,000 a month. If he wants to lift his standard of living (real income), he either needs to make more watches, or increase his profit on each watch. Assuming he can’t lift his profit, he will need to make more watches. Working longer hours is an option, but this is not a productivity gain. A productivity gain occurs when he finds efficiencies to make more in the same amount of time. So, whilst working longer will make you more money, productivity gains are what increase your standard of living in real (inflation adjusted) terms.

Many of the biggest productivity improvements have come from things that have made work easier, such as machines, robots and computers.

Why is it so important?

Economist Paul Krugman said “Productivity isn’t everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.”

Most of Australia’s standard of living increases over the last two decades have come from our terms of trade boom in various commodities, most notably iron ore. Unfortunately, this tailwind appears to be over as our key commodity prices soften.

Therefore, if we want to continue to increase our standard of living, we will need to find productivity gains.

How have we been doing?

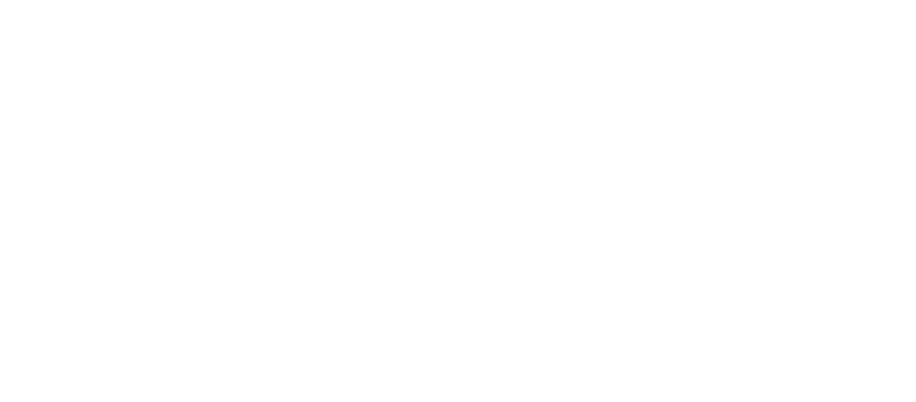

As the chart below shows, productivity hasn’t been great for some time, but from March 2022 to March 2025 we have had the worst productivity performance on record, with a fall of 5.3%. This has seen a significant fall in our real net disposable income per hour and a corresponding decline in our standard of living.

Productivity growth is the key driver of real wages growth in the long run - as this allows real wages to increase.

To understand this better, it may be helpful to come back to our example with Rob the watchmaker. What if he just lifts his prices every year over and above inflation instead of making more watches? Wouldn’t this be an easier way to improve his standard of living? Whilst this may be temporarily possible (and potentially permanent for some rare businesses), when this happens economy wide, all we get is increased inflation. So, whilst Rob increases his earnings by say 5%, if everything Rob buys costs 5% more, Rob is no better off.

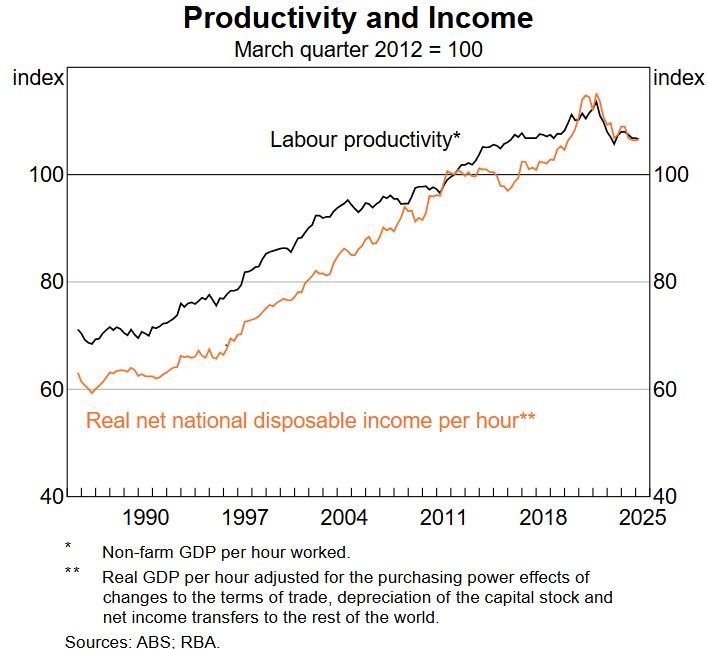

Another way of demonstrating this is the correlation between labour productivity and real per capita consumption over this period. For the first time in decades, per capita consumption in real terms actually fell.

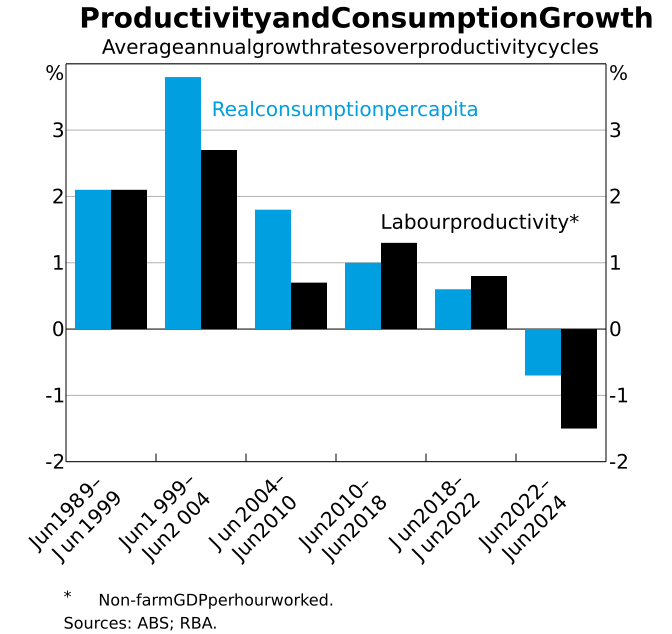

In addition to the inflation issue, there is a competition issue. If other countries are becoming more productive at the same time as we stagnate, the things we make will be comparatively more expensive. All else being equal, this will mean Rob sells fewer watches - ultimately accelerating his decline in living standards.

How are other advanced economies performing? As shown in the chart below, broadly productivity has slowed in most countries with the United States being a notable exception.

There has been extensive work and discussion analysing the reasons for this productivity slowdown. Some of the primary drivers in Australia include:

1. Uncompetitive tax rates - By comparison to other advanced economies, Australia’s corporate income taxes are very high. Our statutory company tax rate (30% for medium and large businesses) is the fourth highest in the OECD.

2. Capital shallowing - Australia has experienced rapid population growth - an increase of 8.7 million people this century, primarily through immigration. However, this influx hasn’t been matched by sufficient investment in infrastructure, housing, machinery, or technology.

3. Weak business investment - Depressed business investment has stalled the growth of Australia’s capital stock. Without robust investment, especially in sectors that drive innovation and efficiency, productivity gains are limited.

4. Expansion of the non-market economy - Government-funded sectors like the NDIS have grown rapidly. While socially beneficial, these sectors typically have lower productivity growth compared to market-driven industries.

5. Soaring energy costs – In particular high gas prices have increased operating costs for businesses, reducing competitiveness and productivity. Industrial energy prices in countries like the US and Canada are less than half that of Australia.

6. Industrial relation policy - Australia’s IR regime has become overly rigid and costly, especially for manufacturing and small businesses. The lack of flexibility in hiring and wage negotiations is seen as a barrier to innovation and efficiency. The Albanese Government’s August 2025 productivity summit explicitly ruled out IR policy from its agenda, despite calls from economists and analysts to address it. This decision was seen as politically cautious and a missed opportunity to tackle structural reform.

7. Regulation - The Productivity Commission and business groups have identified excessive regulation as a major drag on productivity. In a recent speech, Commission Chair Danielle Wood warned that Australia’s “regulatory creep” - the steady expansion of rules and conditional terms in legislation - has dampened growth by prioritising short-term fixes over long-term reform. This sentiment was echoed by Assistant Minister for Productivity Andrew Leigh, who called for “thickets of regulation” to be reduced to improve outcomes.

8. Housing - Australia is experiencing a deep housing crisis, with affordability deteriorating sharply. The average home now costs over $1 million, and the house price-to-income ratio has reached 8.0, meaning the median house costs eight times the median annual household income. This financial strain reduces disposable income, limits consumer spending, and forces workers to live farther from employment hubs, increasing commute times and reducing labour efficiency.

Where is productivity going?

On 12 August, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) cut rates 0.25% to 3.6%. At the press conference post the announcement, the focus was not on the rate cut, but their downgrade of the productivity growth assumptions from 1.0% to 0.7%. This is a 30% reduction in productivity expectations in the medium term. They stated “For some time, our forecasts have implicitly assumed that productivity growth was temporarily weak and would gradually return to, and be sustained at, higher historical growth rates. More often than not, this has not eventuated, resulting in the RBA’s implied productivity forecasts consistently overestimating the actual outcomes… In recognition that some of the lower productivity growth in recent decades is attributable to persistent factors, we are downgrading our medium-term trend productivity growth assumption. We now assume that productivity growth will return to 0.7 per cent by the end of the forecast period, rather than 1.0 per cent.”

This is not an encouraging development. If these forecasts are accurate, this not only results in lower real wages growth, but also increases the risks to inflation being elevated.