Navigating Low Interest Rates

How long will low rates persist?

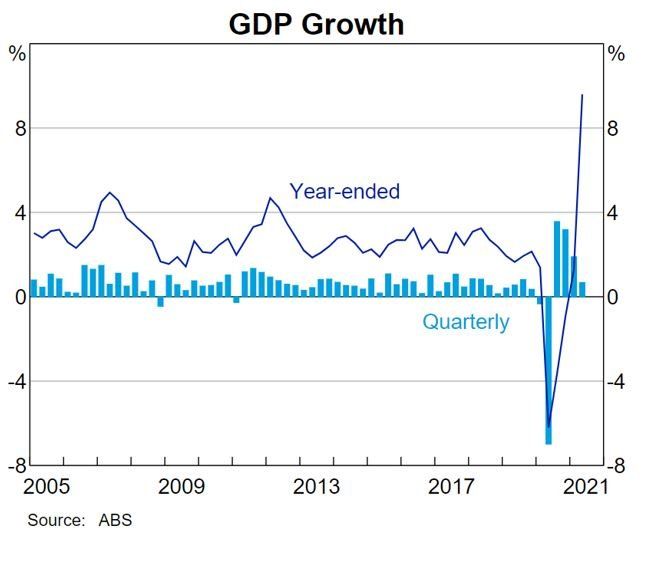

Ultimately no one definitively knows. The best guess historically has been to look at the longer-term interest rate market. This shows that rates will likely be higher than they are today, but materially lower than they have been historically.

The market is factoring in a cash rate of close to 1% by 2024. Interestingly, RBA Governor Phillip Lowe has publicly stated that expectations are too high. For what it’s worth, the market has a better record of predicting rates than the RBA itself.

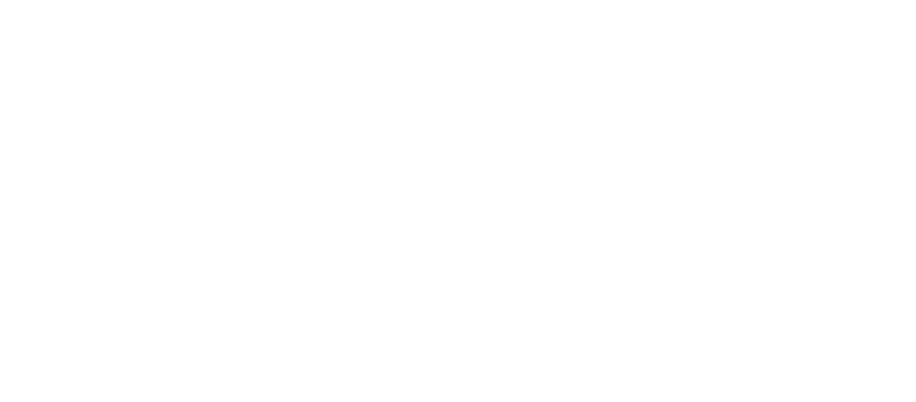

There are a lot of factors that influence rates. The two primary ones being economic growth (GDP) and inflation (CPI). Prior to the most recent lockdowns, both of these measures had rebounded strongly as shown below.

However, the recent lockdowns will see a sharp reversal in the September quarter – obviously this data is yet to be published. As restrictions ease, we would expect to see the recovery resume, however it remains unclear to what extent restrictions will continue to be imposed. This is because we simply can’t know how the virus will evolve – but suffice to say how it evolves will be the primary influencing factor to the direction of the economy and hence interest rates.

Most people would recognise the need to cut rates when faced with last year’s recession. It is less common to recognise the need to normalise rates once the recovery has set in. Therefore, if you believe economic growth will return to trend (or close to trend), you should expect rates to move higher, possibly materially depending on the strength of the recovery.

What are your options?

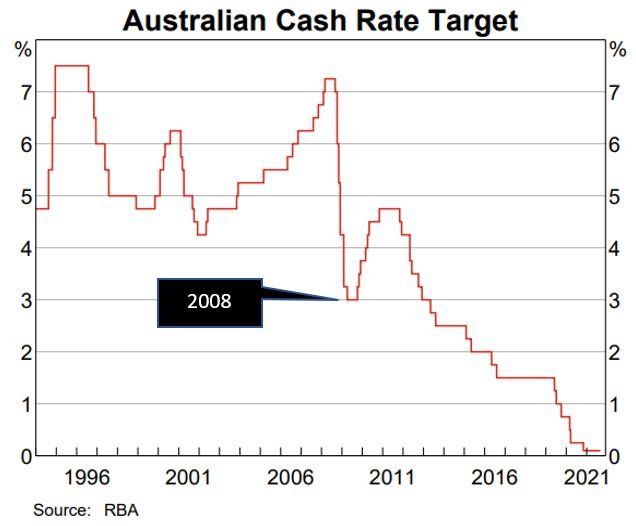

It’s important to understand that whilst it appears there are infinite investment choices, there are really only four broad asset classes to invest in: cash, fixed interest, property and shares.

You should expect over the long term that cash will be the worst performer. Going along the “risk curve” the returns should increase with shares being the best performer. Conversely, cash will have the lowest volatility and once again this increases along the risk curve with shares having the most volatility. Therefore, cash is not chosen for its return attributes, but for its low levels of volatility.

Most people understand this because they’ve observed it – while their shares, property and infrastructure assets perform the best over time, these assets fall the most in times of distress such as the GFC or March 2020. To combat this risk, having some low volatility assets such as cash and bonds will provide a safe liquid asset base that you can draw on, which means you can wait for your other assets to recover as opposed to selling them at greatly reduced prices. What percentage of safe liquid assets you need will vary, but if you’re in retirement and living off your asset base it would be prudent to have a reasonable amount.

Can you get a better return?

In short, the only way is to take on more risk. Investors tend to think about return and risk separately and unfortunately the focus tends to be risk after the market falls and returns after periods of good returns. This is despite history showing us very clearly that the time to focus on risks is after periods of good returns and the time to focus most on returns is after large falls.

Reducing exposure to cash and bonds and increasing your exposure to shares, property and infrastructure will likely result in higher long-term returns. However, it will only do so as long as you do not need to liquidate these positions at times of distress – which may not be an option if you need to draw on your assets.

Therefore, if you are going to explore changes to your asset allocation to increase returns, be very clear why you are pursuing them and understand the downsides to this strategy before implementing any changes.

A cautionary note about Corporate Bonds

Due to the low returns offered in cash and Government bonds we are seeing many investors starting to replace these assets with corporate bonds. We believe they are doing so with the false belief that this is a way of getting better returns without any real increases in risk. History tells a very different story. A corporate bond (sometimes called credit or debt) is effectively a loan to a business, while a Government bond is a loan to the Government.

The key differences between corporate and Government bonds:

1. Corporate bonds have a higher yield (interest payments) than Government bonds. The less credit worthy the business, the higher the yield

2. In times of distress corporate bonds fall in value, often dramatically. Government bonds typically rise in value as investors flock to safety, driving the price higher.

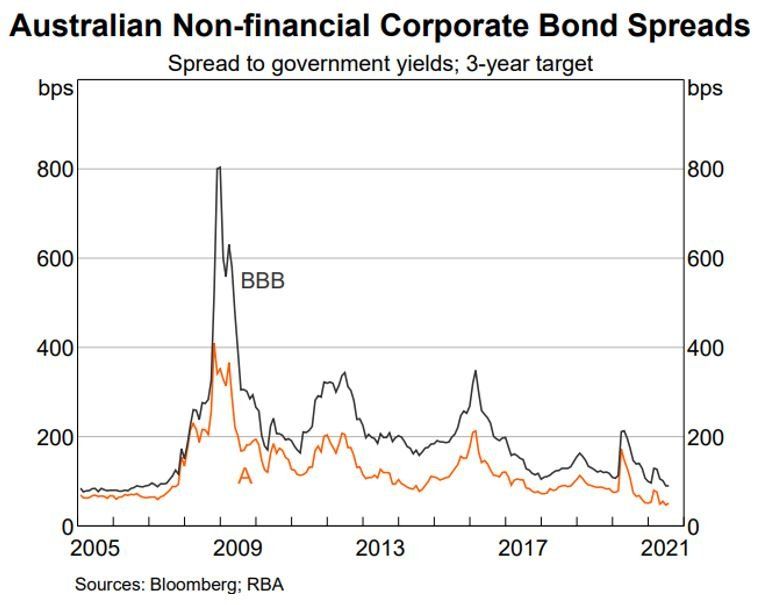

The chart below shows the spread (difference) in yield between a corporate bond and a Government bond. The Government bond is set at the zero line. When the lines rise dramatically as they did in 2008 the value of your corporate bond fell as dramatically!

As you may observe, these credit spreads increase at exactly the same time as the share market falls. Therefore, if your original reason for holding cash and Government bonds was for a source of safe liquid funds that you can draw on in times of distress – corporate bonds are not a substitute.

In addition, spreads (prices) currently imply the upside is only marginally better than the alternative safe asset. A “BBB” corporate bond will return a little over 1% at the moment versus a term deposit of say 0.4%. However, the downside of BBB corporate bond may be a negative 50% if the GFC is any guide. This type of return profile could be best described as “picking up pennies in front of a slow-moving steam roller”.

Whilst we think there is a time and a place for this asset class, it is important investors understand the very significant differences between ‘cash and Government bonds’ and ‘corporate bonds’ before investing.