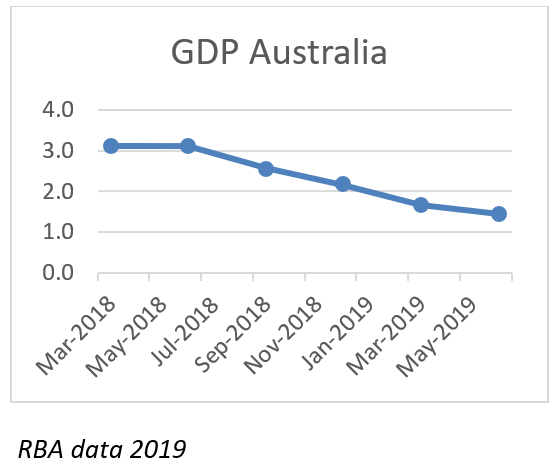

We reported in the April Newsletter that Gross Domestic Product (GDP) had slowed in the last half of 2018. Since then we have seen economic growth in Australia continue to deteriorate. The RBA data shows year end GDP growth was recorded at 3.1% in March of 2018 and has continued to fall to its current 1.4% in September 2019. GDP was last this low in September 2009.

Economic growth has slowed and share markets around the world are experiencing an increased level of volatility.

Sensationalist media reporting exacerbate fear of market volatility. Our observation is that media will apply an intense short term focus on specific events and use very emotive language to explain their story.

It is understandable how this would be the case. Journalists are incentivised to have their report read widely so they sell more than their competitor. To illustrate this point, the market cap or the collective value of companies listed on the ASX at end of Aug 2019 was 2,074,246 million! That is a little over 2 trillion dollars.

If the market moved 2% that means the market would have “lost” or “gained” over $40 billion dollars. Is this a crash, or a windfall?

It is certainly a very big number, but it is explaining a proportion of an enormous number. It is not helpful to report in percentages and then make an issue about the absolute number. When thinking about an investment portfolio, a swing of 2%, is not unusual, in fact over time investors should expect larger daily movements than this. Whilst very few like volatility, it’s an unavoidable part of investing.

Volatility measures have a use, but they should largely be ignored when making long term decisions around your portfolio settings. We need to remember that as investors we must see events through the lens of a much longer timeframe than the media reports presented to us each day.

Slowing growth?

The data supports the media coverage that the domestic economy is slowing. However, we should recognise that these are lagging metrics and they tell us what has happened and not what is going to happen in the future.

The RBA has already reduced rates and the government has legislated the lower tax rates promised in the recent election.

While we won’t touch on the tax cuts any further in this newsletter suffice to say they are stimulatory, and their impact is yet to be included in the economic data.

Rate cuts

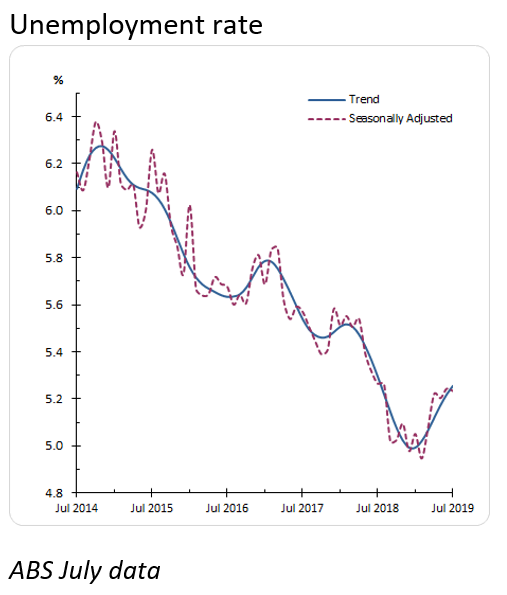

How do lower rates stimulate growth? Lowering interest rates reduces the cost of money. For companies and individuals with debt this will reduce their interest payments, giving them more money to invest and or spend. It also decreases the attractiveness of leaving money in the bank and increases the attractiveness of taking on new debt, which will hopefully be used to make investments into productive opportunities that employ more people. The maintenance of full employment is one of the pillars of the RBA mandate.

The RBA lowered interest rates in June and again in July bringing them to 1%. These cuts are the first time the RBA has moved the cash rates since the last reduction in August 2016. The market is pricing rates in the expectation they will reduce further to perhaps 0.5% or even lower. Should further cuts be required it is expected they will be made in the next 6 to 9 months.

An RBA cash rate of 0.5% will be at the lower range of the capacity for interest rates alone to provide stimulus to the Australian economy. It is likely that should rates get this low we will see the RBA introduce some form of Quantitative Easing (money printing) to bolster the stimulus sought from low rates alone.

Remember in simple terms a slowing economy gives cause for a lowering of interest rates to stimulate growth, while a growing economy gives cause to increasing rates to offset the risk of cost pressures, improved growth in the economy and inflation.

The recent rate cuts (along with some relaxation of the credit rules), has already given a boost to the volume of credit and associated house prices.

RBA data shows investor lending has increased in July. Unsurprisingly so has median house prices with capital cities increasing at an annualised pace of a touch over 6%. While investment into unproductive assets such as existing housing is not necessarily healthy for an economy, it remains an indicator that the reduction in interest rates has increased the flow of money into the economy.

Free market forces remain the most efficient manner to encourage the allocation of money towards productive economic activity. Governments cannot mandate growth. At best Governments can incentivise economic activity in a specific sector but it will always be the market that defines if this activity becomes a productive use of this capital.

In our view, simply increasing the supply of money though reduction in the price [of money] is more likely to inflate the price of existing assets than increase productivity. At some point Australia is going to have to have a discussion around further fiscal initiatives and microeconomic reform as tools to increase productivity.

Time will tell us if this, and future, stimulus will be enough to prevent Australia recording its first recession in over 28 years. However, should we still record the necessary 2 consecutive quarters of negative growth required to form a technical recession, the measures taken to date are likely to shorten any recession and limit the negative impact on the economy.

Valuations

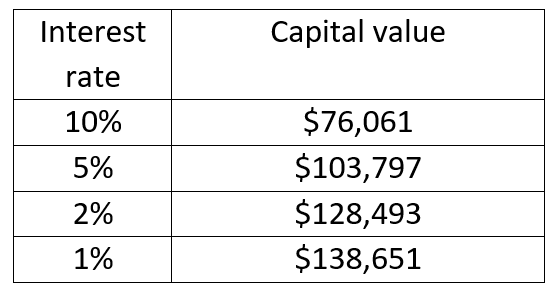

Interest rates are also the key to placing a value on companies or indeed the value of any asset. When investing in an asset you are putting up a lump sum for a future cashflow. When valuing that future cashflow a higher interest rate will give you a lower lump sum value and a lower interest rate will give you a higher lump sum value.

Consider an industrial property that has a lease guaranteed to pay $10,000 p.a. How much would you pay for that income stream today?

Ignoring things like tax, risk premiums etc. what is the first years cashflow worth in today’s dollars? If interest rates were 10%, you would pay $9,091, which is worked out by calculating the amount you would need to receive today to be in the same position in 1 years time by investing it at 10% i.e. $9,091 plus $909 interest = $10,000

Using 1% you get $9,901, or $810 more. But what about 15 years of $10,000p.a. cashflows?

Using ever lower rates for valuation purposes is courageous and is quite possibly a very expensive assumption. It’s worth reminding people that the benefit of increased valuations as rates fall, will work in reverse as long-term rates rise.

Cash as an asset class

There are of course consequences to stimulus measures that result in cash rates below 1% with low returns on cash being quite topical. Cash as an asset class has no capital component so it is logical that when the income falls to such low levels investors might go looking for higher yield.

However, it is perhaps timely to remember that cash remains integral to the overall asset allocation within your portfolio. Cash provides liquidity, essential in pension phase. In Australia, retail cash accounts are still Government guaranteed up to generous limits. Cash is the only asset that will not change in value in response to a short-term market event. As long-term investors attest, cash gives you options when markets are in a downturn.

Finally whilst the average 6 month term deposit rate is in the region of 1.7%, the 10 year bond rate is 1%. So yes cash returns are low but relative to “safe” Government backed fixed income products they remain reasonable. We would counsel caution towards comparing cash as an asset class to investments in higher yielding debt instruments such as hybrids, corporate debt and mortgage funds. While these assets may provide a higher expected return, they are not cash – these assets typically perform very poorly in an economic slow-down and in fact many of these products became unsellable during the 2008/09 correction. This is exactly the time you typically need liquid cash, as selling shares at this point is undesirable.

Investing in these products requires the investor to have an appetite for volatility and risk of capital loss.