Economic Update - October 2023

In the ever-changing landscape of global economics, we often find ourselves in what can only be described as "interesting times". These words, spoken by Robert Kennedy in 1965, hold a unique relevance today, as inflation takes centre stage in the global economic arena.

It's important to note that while inflation rates might have peaked at 7%, a figure not unfamiliar to those with a longer financial memory, what truly makes these times intriguing is the uncertain path inflation rates are expected to take. Currently, the prevailing belief among mainstream finance commentators is that inflation will gently recede, allowing central banks their ideal soft landing outcome, avoiding harsh economic downturns associated with rapid rate hikes.

However, recent market movements have added a layer of complexity to this narrative. Bond yields, a key indicator of market sentiment, have experienced a sharp rise, challenging the prevailing notion of a gentle inflationary slowdown. The bond market, often a reliable predictor of economic trends, suggests that central banks might not be done tightening their policies just yet.

This newsletter will try to unpack two propositions that we see as important from this observation:

1. Central banks are unable or unwilling to reduce interest rates – interest rates remain high?

2. In the event economic conditions do deteriorate to a point where a response from governments and central banks is expected from the broader population - what actions can they take?

To think this one through we need to consider that any response will sit in two broad categories.

Fiscal response – this is the use of spending or tax policies to influence market conditions or in other words governments spending money to create demand. Some more famous historical spending measures were the construction of halls in schools and insulation schemes in 2008/09 and direct payments to compensate for forced isolation in 2020.

Monetary response – central banks reduce interest rates and/or increase the supply of money. The price of money is at the core of all investment decisions so if the price becomes cheaper then it follows that investment and hence demand should increase. Rates went from a high of 4.75% in October 2011, reducing to 0.1% in December 2020.

The current tightening has taken rates from 0.1% in April 2022 to 4.1% in July 2023. The cost of money has materially increased.

Fiscal response

Governments’ core role is the creation and protection of law, after this they become redistribution machines. Government decisions can be reduced to the basic functions of taxing and spending.

If we consider tax, short term impact can be achieved by waiving future tax liability for specified periods. This is what occurred during the pandemic. Changing tax rules or implementing new taxes to adjust economic decisions are all long-term strategies. Consider the capital gains tax or franking regime that have changed investment decisions over the past 30 plus years.

Spending is the “go to” policy for governments and politicians. It can have an immediate impact on the economy (positive or negative) and is something politicians can announce. Spending or not spending are decisions that are expressed in the budget each year.

Government budgets

Sometimes governments need to spend more than they earn in any given year and to do this they take some of the expected future income and spend it today – in the personal context think of using the credit card for a large, unexpected expense and taking a few months to pay it off.

All budgets recognise the need to spend will not always align with expected revenue. This is why governments will talk about balancing the budget over the cycle or any similar phrase that allows time for future revenue to catch up with today’s “necessary” spending.

This balancing part was briefly touched in 2018 but hasn’t really occurred in a sustained manner since the 2008 financial crisis. Perhaps more importantly both the federal and state budgets have gone into steep deficits since the pandemic and projections show these deficits to continue into the foreseeable future.

When a government decides to spend but the money is not available, they borrow by issuing bonds. A bond is an instrument that will pay the holder a preset amount each month and then the full principal back in the future.

Governments (State and Federal) have borrowed consistently over the past 15 years. Federal Budget papers show that every year since 2008 successive governments have spent more than they have received. The amount of bonds on issue is a direct consequence of these deficits - the money must come from somewhere. Whilst there are short periods where the borrowing has slowed, no part of the debt has been paid back and neither state nor federal governments have announced any intention to commence this process anytime soon.

A bond requires the purchaser receive the full amount at time of maturity. If the government of the day doesn’t have the capacity to pay this back, in cash, then it will refinance. Should the government choose to continue to spend more than they receive it follows that, in time, it will have to refinance all existing debt.

Price of debt

Commentators have to date dismissed the increasingly higher debt levels as immaterial because of the low interest rate environment. This argument always carried an implied assumption that debt could be paid down quickly in the “unlikely” event the price of that debt increased or that revenue continues to strongly grow to cover the expense.

Budget papers show the most recent annual interest expense was $21 billion, implying the average yield of issued bonds is a touch over 2%. This reflects that most bonds currently on issue have been issued prior to 2022 when yields were low.

To give some perspective of the impact of the recent changes in price, if the entire government debt had to be re issued today the interest cost would go from $21 billion to $45.6 billion each year. Perhaps more importantly any fiscal response will require the government issue more debt taking the interest bill even higher.

How long can a government continue to issue debt? Credit quality of the Australian Federal Government as well as the State Governments are not currently in question. However, the situation in Victoria where credit ratings are the lowest in the country is concerning.

The question is what current expenditure will future political parties choose to forego to service the burgeoning interest bill?

Policy makers may need to recognise that inflation has materially increased the cost of money. Whilst it suits a narrative of government and some commentators to discuss this increase as an anomaly, what if it’s not? What if the previous decade of low rates has been the anomaly and the current 4% to 5% cost or higher is the new norm?

Why the increase in debt?

Total debt has increased some $100 billion each year since the 2008 financial crisis. The Federal Government’s own forecast has gross debt passing $1 trillion in the current year (this excludes State debt).

A sustained borrowing program can be indicative of long term economic hardship either domestically or globally. However, RBA data suggests this is simply not the case. Some of the broader indicators show the Australian economy is historically strong.

Terms of Trade measure the ratio of exports to imports. Currently we are at record highs, we are selling more than we are importing by a good margin. This has been attributed to commodity prices, think Iron Ore, Coal, Liquid Natural Gas – the world has been buying our natural resources and paying us handsomely.

Commodity demand is inherently cyclical and longer term reliance can be problematic. There can be only so much iron ore required and presumably with the push to net zero carbon emissions globally, coal and gas will decline in time. The key drivers of our strong terms of trade have been much lower historically.

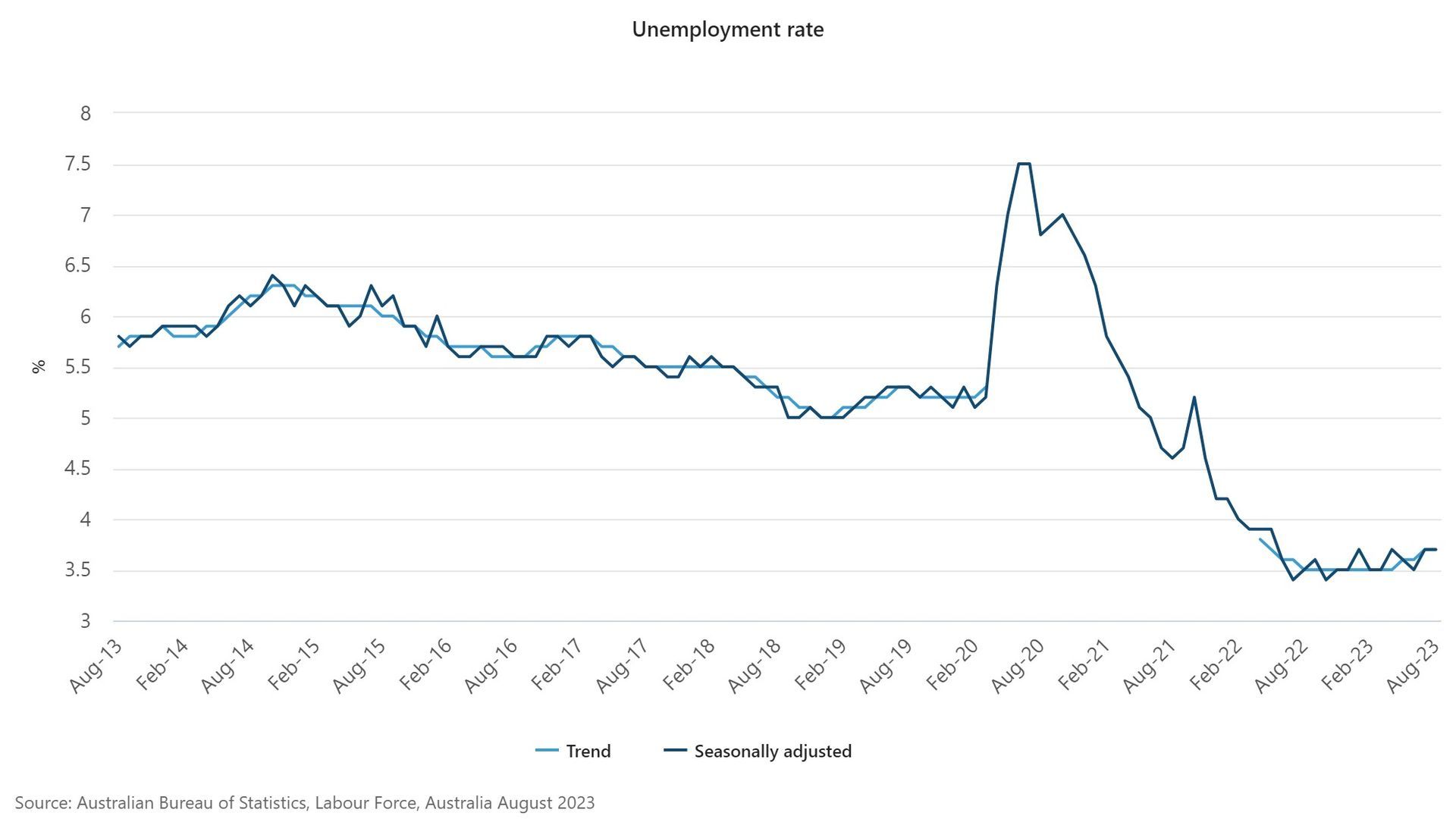

Is it that successive governments have had to spend to prop up a failing labour market? Unemployment can be devastating for communities and there can be a strong moral argument to allow the budget to go into deficit to support the creation of jobs in the economy. But that is not what is happening today.

Australia is experiencing the lowest unemployment in decades. Demand for labour is pushing wages higher as a result. To find demand for labour as strong you need to go back to the post war years of the 1960’s when we had artificial restrictions on who could enter the workforce. What is artificial? Consider pre 1966 when married women could not work in the Commonwealth public service.

So, if we are all at work and as a country, we are also selling more than we are buying, then it must be that our tax system is broken – are we collecting an adequate sum of money from the economic activity being generated?

The data suggests we are doing okay here as well. At best the graph might suggest revenue growth has been volatile because of the disruption from the pandemic but growth in revenue has remained commensurate with the previous decade.

Successive governments have delivered budgets as if the country is in deep economic trouble, but the truth is today we are earning more, more of us are employed and the tax revenue remains historically strong. An outsider looking at this data might well conclude that the economy is strong, our revenue is strong and perhaps we are simply looking at a spending problem!

Productivity

Economic textbooks will argue that an increase in the cost or in the volume of debt has little economic impact as long as that increase in debt is matched by an associated increase in productivity. This is where the phrase “growing the pie” will get used by politicians. The more wealth that is created the more there is to go around.

Productivity is generally measured in terms of how much a business pays to produce a given output. A café makes 100 coffees a day and costs the business $100 to make those coffees. An increase in productivity would mean the café could make 105 coffees for the same $100 outlay. Productivity in this example might have come from improvements in the coffee machine or perhaps efficiency training for the employees.

The concept is that increases in labour costs (paying workers more) is not inflationary when there is also an associated increase in productivity.

The RBA measures unit cost of labour and the data shows Australia is falling behind. Average earnings per hour are shifting slightly higher but productivity per hour is moving sharply lower. Labour productivity per hour is at its lowest point in decades. When inflation is running high employees are understandably seeking increases in wages. But these increases are not being offset by any change in productivity so it stands that there is a strong likelihood wage increases will simply add to the current inflation pressures.

In a world of increasing cost of capital, increases in productivity is where an economy makes up the difference. It might be that the data is showing some short term anomaly, however if this deterioration in labour productivity continues its negative trend, inflationary pressures will also increase.

It is an observation that changes in unit labour costs is an area of the economy that is influenced through changes to industrial relations laws. Industrial relations has been, and continues to be, a strong focus of the current government.

The political position

Successive governments over the last decade and longer have made decisions to lock in expenditure that neither forecasted nor actual revenue can cover. The best example of unconstrained ongoing expenditure is the National Disability Insurance Scheme. The push to renewables is also requiring large budget commitments be carried on the nation’s balance sheet for much longer before the forecasted benefits can offset the cost. Think the Snowy hydro scheme 2.0.

In the event economic conditions deteriorate you would expect Terms of Trade to fall, unemployment to increase and with less people in work, tax revenue to fall. For as long as productivity also deteriorates this scenario will heighten budget sensitivity to debt and interest expense.

You might expect that at some point the population will turn their focus onto those politicians with courage and experience to recognise the current anomalies in our spending and take the hard decisions to address these imbalances. We look forward to seeing which party they turn up in.