Housing and its contribution to inflation

The quarterly consumer price index (CPI) data for the period ending March 2023 was released this week showing inflation has slowed marginally to 7%. Only time will tell if this is sufficient to keep the RBA cash rate at the current 3.6%. A key take out however is to recognise we now have a negative real cash rate of –3.4% (inflation less cash rate).

Inflation is the increase in price between two points in time. To give this some context if you were to assume your expenses are being paid entirely from the interest earned from your cash holdings, then your spending power is reducing by 3.4% each year.

The quarterly release showed price increases across each one of the 14 groups are well in excess of the RBA preferred 2% to 3% band. Housing costs make up 22% of the CPI basket and include rents, new dwellings and electricity. As such this sector will have a large impact on inflation and therefore interest rates themselves. For this reason, we have decided to focus this discussion on housing inflation.

The total value of residential housing in Australia is $9.4 trillion making it the largest single domestic asset and close to three times larger than the total superannuation market. Construction of residential housing is important because it creates flow on effects. Economists call this the “multiplier” effect. Building a house generally requires local tradespeople and local materials. The money those local tradespeople and hardware stores receive is then spent again to purchase groceries and to educate children and so on, resulting in a multiplier of maybe two or three times the initial money spent.

In aggregate, residential construction has one of the highest multipliers across the economy. This is why residential housing is a favourite of successive governments to stimulate economic activity. Think of the first home builders grants and the broader first homeowner grants, the substantial renovations grants during COVID etc.

Rental costs increased by over 5% in March and commentary is noting the associated impact on the social fabric of society. At the individual level the examples of hardship due to lack of housing are real. The commentary implies, however, that the only solution is to increase construction of new dwellings and ignores the average number of people that reside in each existing house.

How many homes do we need? A simple calculation will take the population size and divide it by the average number of people that live in each home. In a perfect world we would then construct more houses in line with the growth in population.

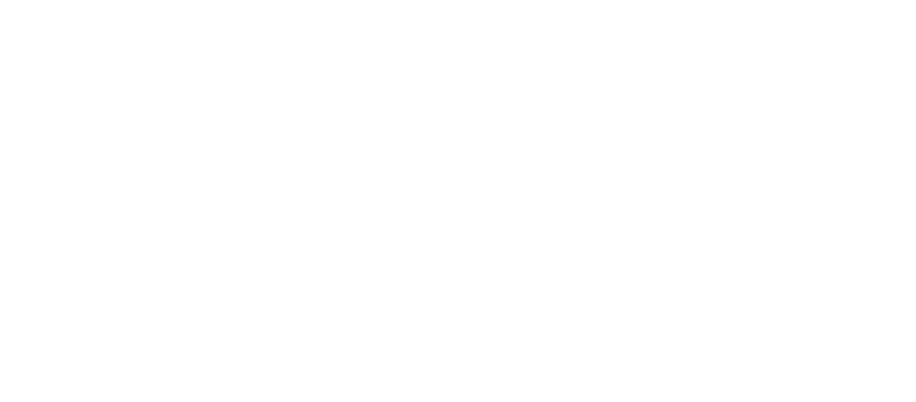

As the chart below shows we have achieved this with dwelling stock largely in-line or above population growth for the past few decades.

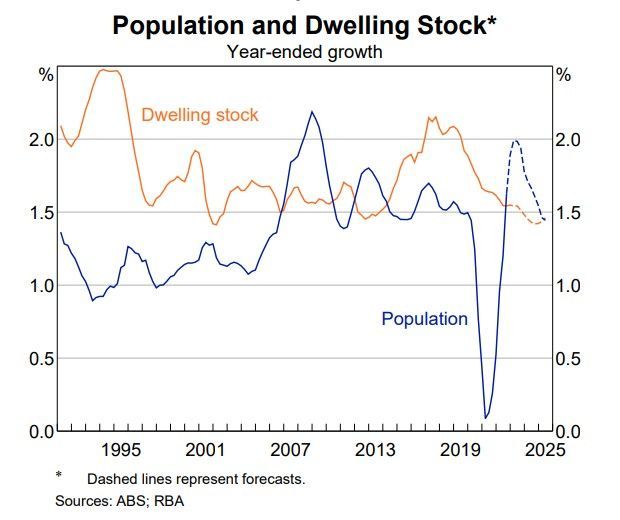

The Covid 19 pandemic forced change in our society. Lockdowns forced us to work from home, JobKeeper, JobSeeker and associated tax breaks subsidised these changed living conditions. Perhaps it was a mix of these incentives, or some other lifestyle choice but by the time the pandemic conditions were lifted there were materially less of us in each home as the graph below shows.

Whilst a reduction of 0.06 people per home doesn’t sound like much, extrapolating that across the country means that we would require about 235,000 extra homes to house the same number of people.

Covid reduced our population growth sharply and this meant the housing shortage due to smaller households was less severe. But as the population growth snapped back it’s no surprise to see why we have the housing shortage we have today.

A solution to alleviate rental pressure is to increase the number of people that live in each house. This is a market forces dilemma. Given time, cost of living pressures caused by inflation might address this apparent imbalance. Interest rates certainly will if they are kept high enough for long enough. Consider the university student that may choose to come back to the family home or an aging parent that might make use of a spare room or perhaps the younger “pre family” workforce choosing to pool resources and share a house.

Like the government housing subsidies that have played a part in increasing house prices, market forces will be tempered by a government looking to alleviate cost of living pressures. Lifestyle decisions such as returning home or pooling resources are only made in reaction to sufficient financial pressure.

If increased average household size can’t eventuate, then we need more houses. Certainly, increasing housing supply is a valid solution but construction takes time. Disregarding the severe inflationary impact of forced building and the challenge to supply materials, labour, release of land and necessary associated infrastructure simultaneously, we cannot expect any material increase in housing supply for many years.

This is the challenge for any government housing programs – stimulating supply of housing and reducing inflationary pressures within the housing sector at the same time is arguably impossible. What of the two remaining variables that influence housing inflation: new house prices and electricity?

Interest rates will eventually constrain increases in house prices provided no further subsidies are thrown at the sector. The capacity to borrow is, and only ever can be, a product of your income and the price of the borrowed money (interest rate). As rates rise your borrowing power decreases, all else remaining the same.

The data shows electricity usage has remained stable in the face of population increases. The price of electricity is what has increased materially. Price is subject to global pressures on the price of coal and natural gas alongside the pursuit of net zero carbon policies. The interaction of these variables within the context of the transition to cleaner energy makes any reduction in the price difficult at least in the medium term.

Inflationary forces in the housing sector are, on balance, lifestyle choices led by the number of people who choose to live together and not solely the number of available houses. It will be interesting how fast we adjust our lifestyle expectations as cost-of-living pressures increase. Material changes will require the Government to have the courage to restrain from subsidising the very costs that are going to influence these lifestyle decisions.